Learning targets:

I can respond thoughtfully to diverse perspectives; synthesize comments, claims, and evidence made on all sides of an issue;

I can propel conversations by posing and responding to questions that probe reasoning and evidence.

I can integrate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media .

I can present information, findings, and supporting evidence, conveying a clear and distinct perspective.

I can analyze nuances in the meaning of words (images) with similar denotations.

I can make strategic use of digital media (e.g., textual, graphical, audio, visual, and interactive elements) in presentations to enhance understanding of findings, reasoning, and evidence and to add interest.

I can adapt speech to a variety of contexts and tasks.

Essential question: How do images augment or distort the truth?

To begin the photojournalism unit, please read the following general information, followed by a brief history of photojournalism.

In order to ensure that the reading has been completed, please respond to the questions that follow. You should be able to copy and paste the responses. Please send along as usual.

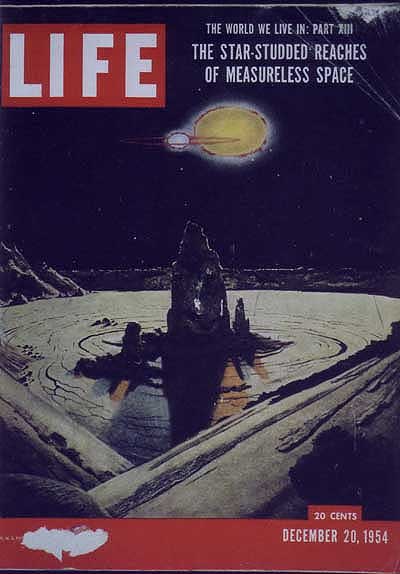

At the end of the blog, you'll find excerpts from Life Magazine's first photojournalism issue.

What is photojournalism?

by Ed Kashi

American photojournalist and member of VII Photo based in the Greater New York area.

Kashi's work spans from print photojournalism to experimental film. He is most noted

for documenting sociopolitical issues.

Photojournalism is a unique and powerful form of visual storytelling originally created for print magazines and newspapers but has now morphed into multimedia and even documentary film making. Through the internet, apps and the mobile device explosion, photojournalism can now reach audiences never before imagined with immediate impact, while continuing to write our visual history and form our collective memories.

Photojournalism works on multiple levels, from covering breaking news and wars, to forming visual narratives and feature stories that help to illuminate and clarify the issues of our time with a depth and perspective that few other mediums can achieve. The universal nature of photography and the ability to capture time and freeze it in a way the mind remembers is a searing and unique quality of this medium.

Photojournalism can also work as an agent of change, often outside of its role in mainstream media. This tradition harks back to its earliest days and confirms its roots in advocacy and the documentary tradition. When practiced as long form, in depth, personal storytelling, photojournalism expands the aesthetics of visual reporting, justifies its grand intentions of enlightenment and contributes to our deeper understanding of the world.

...........................................................................................

More info..

Photojournalism is a branch of journalism characterized by the use of images to tell a story. The images in a piece may be accompanied by explanatory text or shown independently, with the images themselves narrating the events they depict. Photojournalists can be found working all over the world, from the halls of the White House to the steppes of Asia, and they deal with a broad assortment of situations on a daily basis. Many major newspapers have photojournalists on staff, and others rely on photographs included in a press pool by freelance photojournalists.

People have been using images to depict events for centuries, from rock paintings to engravings in major newspapers. The first big event to be captured in photography was the Crimean War, establishing the groundwork for the professional field. Initially, photographs were often used to accompany text stories to provide some variation and visual interest, but over time, images began to be used more exclusively to narrate stories in the media.

The field is distinct from that of documentary photography. Although both involve taking photographs which are objective, honest, and informative, photojournalism involves photographing specific events, while documentary photography focuses on ongoing situations. A photographer who follows traditional farmers in rural England is a documentary photographer, but one who takes pictures of the aftermath of a suicide bombing for publication in the news is a photojournalist.

Modern photojournalism: 1920-1990.

excerpts from from Ross Collins, professor North Dakota State University, advanced News Photography Course

1925 Leica

The beginning of modern photojournalism took place in 1925, in Germany. The event was the invention of the first 35 mm camera, the Leica. It was designed as a way to use surplus movie film, then shot in the 35 mm format. Before this, a photo of professional quality required bulky equipment; after this photographers could go just about anywhere and take photos unobtrusively, without bulky lights or tripods. The difference was dramatic, for primarily posed photos, with people award of the photographer's presence, to new, natural photos of people as they really lived.

Added to this was another invention originally from Germany, the photojournalism magazine. From the mid-1920s, Germany, at first, experimented with the combination of two old ideas. Old was the direct publication of photos; that was available after about 1890, and by the early 20th century, some publications, newspaper-style and magazine, were devoted primarily to illustrations. But the difference of photo magazines beginning in the 1920s was the collaboration--instead of isolated photos, laid out like in your photo album, editors and photographers begin to work together to produce an actual story told by pictures and words, or cutlines. In this concept, photographers would shoot many more photos than they needed, and transfer them to editors. Editors would examine contact sheets, that is, sheets with all the photos on them in miniature form (now done using Photoshop software), and choose those he or she best believed told the story. As important in the new photojournalism style was the layout and writing. Cutlines, or captions, helped tell the story along with the photos, guiding the reader through the illustrations, and photos were no longer published like a family album, or individually, just to illustrate a story. The written story was kept to a minimum, and the one, dominant, theme-setting photo would be published larger, while others would help reinforce this theme.

The combination of photography and journalism, or photojournalism--a term coined by Frank Luther Mott, historian and dean of the University of Missouri School of Journalism--really became familiar after World War II (1939-1945). Germany's photo magazines established the concept, but Hitler's rise to power in 1933 led to suppression and persecution of most of the editors, who generally fled the country. Many came to the United States.

The time was ripe, of course, for the establishment of a similar style of photo reporting in the U.S. Henry Luce, already successful with Time and Fortune magazines, conceived of a new general-interest magazine relying on modern photojournalism. It was called Life, launched Nov. 23, 1936.

The first photojournalism cover story was an article about the building of the Fort Peck Dam in Montana. Margaret Bourke-White photographed this, and in particular chronicled the life of the workers in little shanty towns spring up around the building site. The Life editor in charge of photography, John Shaw Billings, saw the potential of these photos, showing a kind of frontier life of the American West that many Americans thought had long vanished. Life, published weekly, immediately became popular, and was emulated by look-alikes such as Look, See, Photo, Picture, Click, and so on. Only Look and Life lasted. Look went out of business in 1972; Life suspended publication the same year, returned in 1978 as a monthly, and finally folded as a serial in 2001.

But in the World War II era, Life was probably the most influential photojournalism magazine in the world. During that war, the most dramatic pictures of the conflict came not so often from the newspapers as from the weekly photojournalism magazines, photos that still are famous today. The drama of war and violence could be captured on those small, fast 35 mm cameras like no other, although it had to be said that through the 1950s and even 1960s, not all photojournalists used 35s. Many used large hand-held cameras made by the Graflex Camera Company, and two have become legendary: the Speed Graphic, and later, Crown Graphic. These are the cameras you think of when you see old movies of photographers crowding around some celebrity, usually showing the photographer smoking a cigar and wearing a "Press" card in the hatband of his fedora. These cameras used sheet film, which meant you had to slide a holder in the back of the camera after every exposure. They also had cumbersome bellows-style focusing, and a pretty crude rangefinder. Their advantage, however, was their superb quality negative, which meant a photographer could be pretty sloppy about exposure and development and still dredge up a reasonable print. (Automatic-exposure and focus cameras did not become common until the 1980s.)

Rolleifex

Successor to the Graphic by the 1950s was the 120-format camera, usually a Rolleiflex, which provided greater mobility at the expense of smaller negative size. You looked down into the ground-glass viewfinder. But in newspapers, by the Vietnam War era, the camera of choice was the 35--film got better, making the camera easier to use, and the ability to use telephone, wide-angle, and later, zoom lenses made the 35 indispensable, as it still is to most photojournalists today.

35 mm

Some of the great photojournalists of the early picture story era included "Weegee" (Arthur Fellig), a cigar-chomping cameraman before World War II who chronicled the New York crime and society's underside.

During World War II W. Eugene Smith and Robert Capa became well known for their gripping war pictures. Both were to be gravely affected by their profession. In fact, Capa was killed on assignment in Indochina, and Smith was severely injured on assignment in Japan.

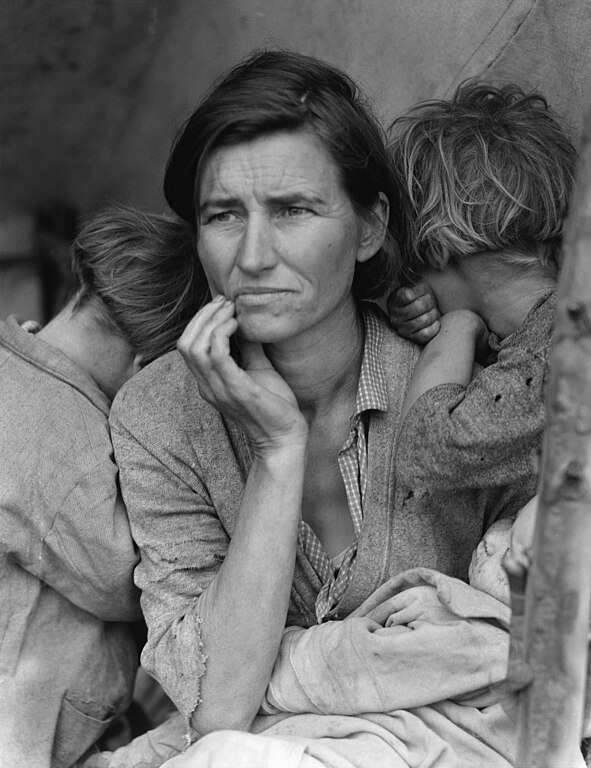

Shortly before the war, with the world realizing the power of the camera to tell a story when used in unopposed, candid situations, the federal government's Farm Security Administration hired a group of photographers. In fact, the FSC was set up in 1935 by Franklin D. Roosevelt to help resettle farmers who were destitute due to the Depression and massive drought in the Midwest. Because these resettlements might be a controversial task, the director, Roy Stryker, hired a number of photographers to record the plight of the farmers in the Midwest.

The photographers later, many of them, became famous--the collected 150,000 photos now housed in the Library of Congress. The power of these often stark, even ugly images showed America the incredible imbalance of its society, between urban prosperity and rural poverty, and helped convince people of the importance of Roosevelt's sometimes controversial social welfare programs. You can still buy copies of all these photos from the Library of Congress, including the most famous, such as Arthur Rothstein's dust bowl photo, or Dorthea Lange's "Migrant Mother."

The golden age of photojournalism, with its prominent photo-story pages, ranged from about 1935 to 1975. Television clearly had a huge impact--to be able to see things live was even more powerful than a photo on paper. Even so, many of the photos we remember so well, the ones that symbolized a time and a place in our world, often were moments captured by still photography. Early in photojournalism black and white was still the standard, and newspapers and many magazines were still publishing many photo-pages with minimal copy, stories told through photographs. Beginning about in the mid-1980s, however, photojournalism changed its approach. Photographs standing alone, with bare cutlines, carrying the story themselves often have been dropped in favor of more artistic solutions to story-telling: using photography as part of an overall design, along with drawings, headlines, graphics, other tools. It seems photography has fallen often into the realm of just another design tool.

Photography is driven by technology, always has been. Because, more than any other visual art, photography is built around machines and, at least until recently, chemistry. By the 1990s photojournalists were already shooting mostly color, and seldom making actual prints, but use computer technology to scan film directly into the design. And by the beginning of the new millennium, photojournalists were no longer using film: digital photography had become universal, both faster and cheaper in an industry preoccupied with both speed and profit. If you compare published photography today to that to 25 years ago, many fewer candid photos, less spontaneity, fewer feature photos of people grabbed at work or doing something outside.

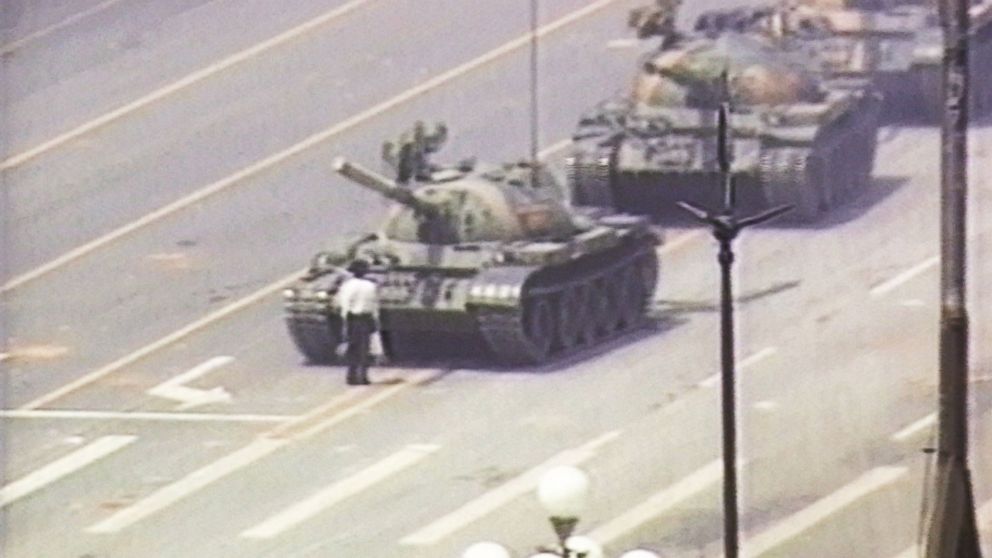

You'll also find that the quality of the image has gone up, better lighting, sharper focus, and lush color, especially primary colors. Is photojournalism better today than it was in the black and white days? It depends on what you like. Perhaps still photojournalism is not as important to society today, does not have the general impact of television, and its sometimes gritty "you are there" images bounced off satellite. Still, even with all our space-age technology, remember an image that for you defined a certain event, chances are you'd remember a still photograph. For instance, think Tiananmen Square in China, and you'd possibly recall the man facing down tanks. Think Gulf War, and you may recall the wounded soldier crying over a comrade. Think Vietnam War, and the execution of a Vietcong, or girl napalm victim. Think Protest Era, and the woman grieving over students shot at Kent State University. The single image still holds some defining power in our society.

Photojournalism background information questions

1. What was the original purpose of photojournalism and how has it changed?

2. What is the difference between photojournalism and documentary photography?

3. How did the Leica change photography?

4. How did the photo magazines differ from individual news photos?

5. What was the function of the cutlines?

6. Who was Henry Luce?

7. How has photojournalism served political or social issues?

8. What was the impact of television on photojournalism?

9. In what way is photography “another design tool?”

10. What role does photojournalism play now?

No comments:

Post a Comment